ZenStack - The Next Chapter (Part II. An Extensible ORM)

In the previous post, we discussed the general plan for ZenStack v3 and the big refactor. This post will explore the extensibility opportunities the new architecture brings to the core ORM.

In the previous post, we discussed the general plan for ZenStack v3 and the big refactor. This post will explore the extensibility opportunities the new architecture brings to the core ORM.

Back in late 2022, when Jiasheng and I discussed how to make building web apps less painful, we initially thought of building something for people without a programming background. We eventually couldn't convince ourselves it could work, so we decided to take a step back and try to make developers' lives easier. That "step back" became the start of ZenStack.

The past two and half years have been full of joy and fulfillment. By building the tool, seeing how people use it, and learning what works and what doesn't, we've got a better understanding of the intricacy of "easy". What people need is not just writing less code or shipping faster, but rather an inexplicable balance between low cognition burden and high flexibility. We are probably on the right track to solving the problem, but there's still a long way ahead. While considering what to do in V3, we think it's a good time to better align ZenStack's architecture with the ultimate goal.

In the early days of web and mobile app development, building a backend from scratch was laborious and error-prone. Developers had to manage servers, databases, and infrastructure and ensure scalability while writing the core business logic of their applications. Then came BaaS(Backend-as-a-Service), promising to liberate developers from this burden.

React Table, or more precisely, TanStack Table is a headless table UI library. If you're new to this kind of product, you'll probably ask, "What the heck is headless UI"? Isn't UI all about the head, after all? It all starts to make sense until you try something like React Table.

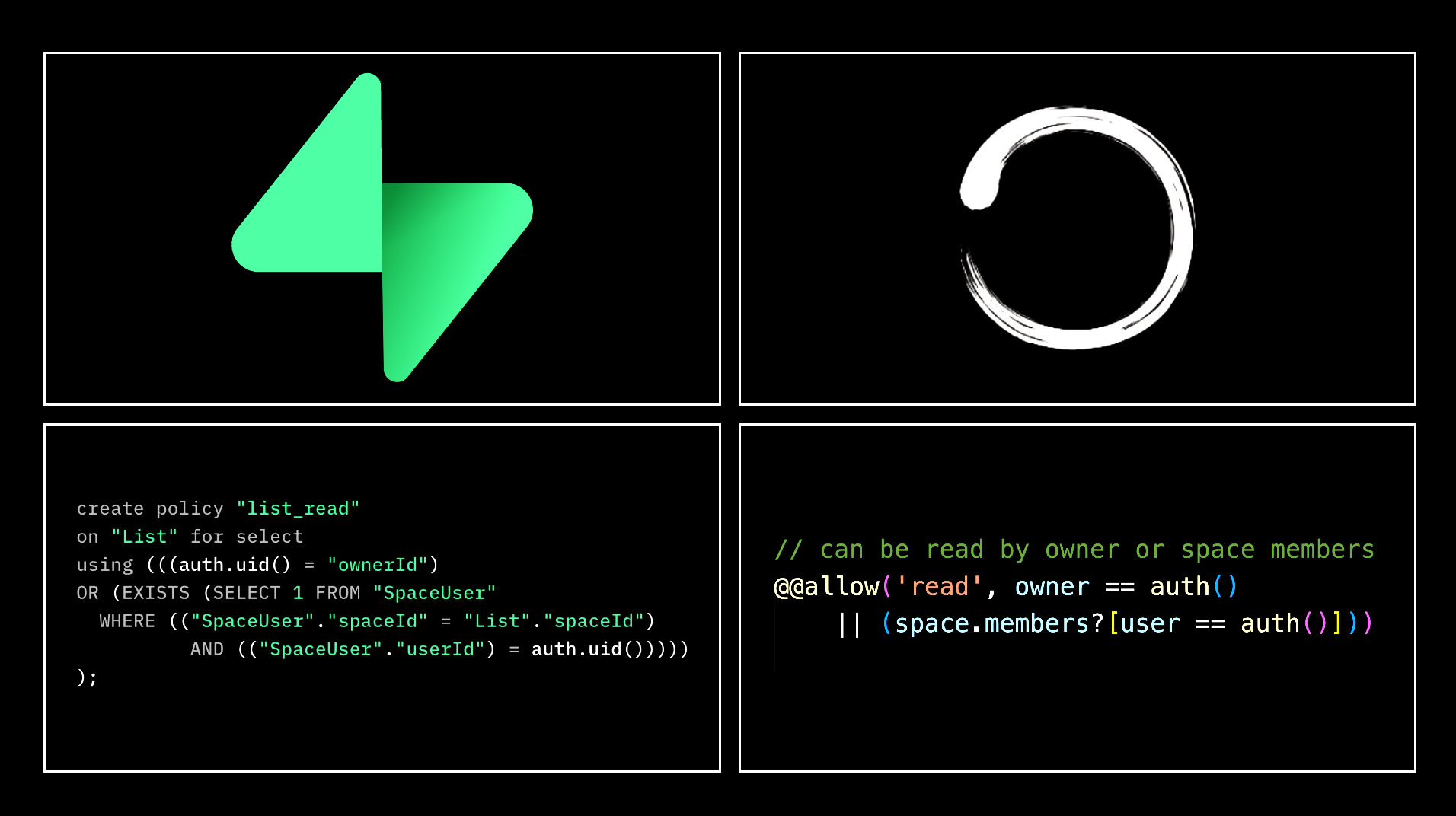

Among ZenStack's features, the most beloved one is the ability to define access control policies inside the data schema. This ensures that your rules are colocated with the source code, always in sync with the data model, and easy to understand. It arguably provides a superior DX to other solutions like hand-coded authorization logic, or Postgres row-level security.

However, as your application grows more complex, you may find yourself repeating the same policy patterns across multiple models. This post explores one typical pattern of such duplication and demonstrates how the new check() attribute function can help you keep your policies DRY.

After polishing ZenStack V2 in the future branch for more than two months, we are happy to make it official now. I would like to take this opportunity to briefly show you the main features of V2 and the stories behind it.

As software developers, we are all familiar with the phrase "Don't reinvent the wheel". However, I have heard many complaints that the Javascript world seems to do the exact opposite. 😂

As a software developer, you may not have directly participated in any open-source project, but you have likely benefited from the open-source world unless you don't use Git, GitHub, or Linux. 😄 In return, many of us would like to contribute and be a part of this new wave of collaborative and transparent development.

Having been involved in the development of four commercial SaaS products at my previous company, I've come to realize the multitude of complexities that arise compared to typical consumer products. Among these complexities, one prominent area lies in the intricate realm of permission control and access policies.

Have you ever built a product from scratch? If so, I bet you definitely experienced the trade-off between the design quality and time to market. In fact, you might have to struggle with it more than you expected. In Shopify's practice Deconstructing the Monolith: Designing Software that Maximizes Developer Productivity, they get the conclusion below:

In conclusion, no architecture is often the best architecture in the early days of a system. This isn’t to say don’t implement good software practices, but don’t spend weeks and months attempting to architect a complex system that you don’t yet know. Martin Fowler’s Design Stamina Hypothesis does a great job of illustrating this idea, by explaining that in the early stages of most applications, you can move very quickly with little design. It’s practical to trade off design quality for time to market. Once the speed at which you can add features and functionality begins to slow down, that’s when it’s time to invest in good design.